Cordoba is a city in Andalusia in Southern Spain and the capital of the province of Cordoba.

It is the third most populated municipality in Andalusia, after Sevilla and Malaga, and the 11th overall in the country.

It was a Roman settlement on the right bank of the Guadalquivir, taken over by the Visigoths,

followed by the Muslim Conquests in the eighth century and later becoming the capital of the Umayyad Caliphate of Cordoba.

During these Muslim Periods, Cordoba was transformed into a world-leading center of education and learning,

producing figures such as Averroes, Ibn e Hazm, and Al Zahrawi and by the 10th century,

Then it had grown to be the second-largest city in Europe.

Following the Christian conquest in 1236. So, it became part of the Crown of Castle.

It is home to notable examples of Moorish Architecture such as the great mosque of Cordoba which was named a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1984 and is now a cathedral.

The UNESCO status has since been expanded to encompass the whole Historic city of Córdoba, Madina-e-Azahara and Festival de los Palitos.

It has the highest summer temperatures in Spain and Europe with average high temperatures around 37 °C (99 °F) in July and August.

Cordoba has more World Heritage Sites than anywhere in the world.

Much of this architecture, such as the Alcazar and the Roman Bridge has been reworked or reconstructed by the city’s successive inhabitants

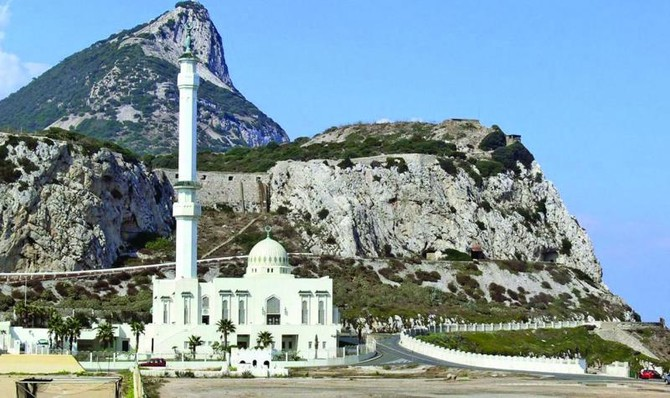

The Great Mosque of Cordoba, officially known by its ecclesiastical name, is located in the Spanish region of Andalusia.

Due to its status as a former Islamic mosque, it is also known as the Mezquita and as the Great Mosque of Córdoba.

According to traditional accounts a Visigothic church, the Catholic Christian Basilica of Saint Vincent of Saragossa, originally stood on the site of the current Mosque-Cathedral, although the historicity of this narrative has been questioned by scholars.

The Great Mosque was constructed on the orders of Abd ar-Rahman I in 785 CE when Córdoba was the capital of the Muslim-controlled region of Al-Andalus. It was expanded multiple times afterward under Abd ar-Rahman’s successors up to the late 10th century. Among the most notable additions,

Abd ar-Rahman III added a minaret and his son Al-Hakam II added a richly-decorated new mihrab and maqsura section. The mosque was converted to a cathedral in 1236 when Córdoba was captured by the Christian forces of Castile during the Reconquista.

"Burn your boats," said Tariq bin Ziyad while addressing his small army after entering Spain through sea in 711 A.D. The order was instantly followed by his forces despite a huge army of opponents ready to attack them. This ultimate trust in Allah and a strong determination to fight for a just cause was aptly demonstrated by Tariq, apparently giving birth to the above-mentioned maxim. “My Dear brothers, we are here to spread the message of Allah. Now, the enemy is in front of you and the sea behind. You fight for His cause. Either you will be victorious or martyred. There is no third choice. All means of escape have been destroyed,” he thundered while addressing his forces before the battle began. The victory of Islam following the acts of valor, as well as piety, was imminent. Tariq bin Ziyad was a new convert to Islam from the Berber tribe of Algeria. He was said to be a freed slave. Islam provided high status even to slaves. Salman Farsi, Bilal ibn Rabah and Zaid ibn Harithah were slaves before being freed during time of the Holy Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him). Salman Farsi was appointed Governor of Madayen. Bilal was known for his beautiful voice with which he called people to their prayers. Zaid led a force during the Battle of Mauta. Even in the later period, the Mamalik (slaves) ruled Egypt and Qutubuddin Aibak established his dynasty in India and ruled for centuries. Tariq bin Ziyad is believed to be belonging to the Ash-Shadaf Berber tribe from North Africa. He was probably born in 50 AH. Historian Ibn Idhari, however, states that he was from the Ulhasa tribe. Ibn Khaldun has written that the Ulhasa tribe was found on both sides of the Tafna river in Tlemcen, Algeria. Tariq bin Ziyad is considered to be one of the most important military commanders in the Iberian history. It is said that he saw the Holy Prophet (peace be upon him) in his dream who saying: “Take courage, O Tariq! And accomplish what you are destined to perform.” Then he saw the Messenger of Allah (peace be upon him) and his companions entering Andalus.” Tariq awoke with a smile, and from that moment, he never doubted his victory. He led a small force from Morocco in 711 AD and landed on the high rock which is called Jabal-Al-Tariq (Gibralter) after his name in Spain. The army of Tariq, comprising 300 Arabs and 10,000 Berber converts to Islam, landed at Gibraltar. King Roderic of Spain amassed a force of 100,000 fighters against the Muslims. Tariq called for reinforcements and received an additional contingent of 7,000 cavalrymen under the command of Tarif bin Malik Naqi (after whom Tarifa is named in Spain). When Tariq bin Ziyad found the Muslim ranks a bit nervous in the face of the large enemy in front of them, he ordered the ships to be burned and then delivered the historic and stirring address to the Mujahedeen. The two armies met at the battlefield of Guadalete where King Roderic was defeated and killed on Ramadan 28, 92 AH. The defeated Spanish army retreated toward Toledo. Tariq bin Ziyad divided his troops into four regiments for a hot pursuit. One regiment advanced toward Cordoba and subdued it. The second captured Murcia and the third advanced toward Saragossa. Tariq himself moved swiftly toward Toledo. The city surrendered without resistance. King Roderic’s rule came to an end in Spain. Upon hearing the grand victory, Commander Musa bin Nusair rushed to Spain with another large force of 18,000. The two generals occupied more than two-thirds of the Iberian Peninsula In rapid succession, Saragossa, Barcelona and Portugal fell one after another. Later, the Pyrenees was crossed and Lyons in France was occupied. Spain remained under Muslim rule for more than 750 years, from 711 to 1492. In its swiftness of execution and completeness of success, Tariq’s expedition into Spain holds a unique place in the medieval military annals of the world. Muslim rule was a major boon to local residents. No properties or estates were confiscated. Instead, the Muslims introduced an intelligent system of taxation, which soon brought prosperity to the peninsula and made it a model country in the West. The Christians had their own judges to settle their disputes. All communities had equal opportunities for entry into the public services. The Jews and the peasants in Spain received the Muslim armies with open arms. The serfdoms that prevailed were abolished and fair wages were instituted. Taxes were reduced to a fifth of the produce. Anyone who accepted Islam was relieved of his slavery. A large number of Spaniards embraced Islam to escape the oppression of their masters. The religious minorities, the Jews and the Christians, received the protection of the state and were allowed participation at the highest levels of the government. As result of Muslim rule, Spain became a beacon of art, science and culture for Europe. Mosques, palaces, gardens, hospitals and libraries were built. Canals were repaired and new ones were dug. New crops were introduced from other parts of the Muslim empire and agricultural production increased. Andalus, as Spain was called by Muslims, became the granary of the West. Manufacturing was encouraged and the silk and brocade work of the peninsula became well known in the trading centers of the world. Cities increased in size and prospered. Cordoba, the capital, became the premier city of Europe and by the 10th century, had over one million inhabitants. A Christian historian writes: "The Moors (Muslims) organized that wonderful kingdom of Cordova, which was the marvel of the Middle Ages, and which, when all Europe was plunged in barbaric ignorance and strife, alone held the torch of learning and civilization bright and shining before the Western world."

When the young and stout-hearted Muslim General, Tariq Bin Ziad, landed with his Arab soldiers on the coast of Spain, he ordered the vessels in which they had crossed the Mediterranean to be burnt, so that there remained no possibility of a retreat. After the command had been carried out, he addressed his troops in these memorable words:

“There is no escape now. The sea is behind you and the enemy is in front. By God! you have nothing to depend upon except your own courage and fortitude.”

Córdoba was conquered by the Muslims in 711 or 712. Unlike other Iberian towns, no capitulation was signed and the position was taken by storm. Córdoba was in turn governed by direct Arab rule. The new Umayyad commanders established themselves within the city and in 716 it became the provincial capital, subordinate to the Caliphate of Damascus, replacing Seville. In Arabic it was known as قرطبة (Qurṭuba).

The center of the Roman and Visigothic cities became the walled medina. Over time, as many as 21 suburbs (رَبَض rabaḍ, pl. أَرْبَاض arbāḍ) developed around the city.

In 747, a battle in the surroundings of Córdoba, the Battle of Saqunda, took place, pitting Arab Yemenites against northerner Qays.

Abd ar-Rahman I became emir of Córdoba in 756 after six years in exile after the Umayyads lost the position of caliph in Damascus to the Abbasids in 750. Intent on regaining power, he defeated the area’s existing Islamic rulers and united various local fiefdoms into an emirate. Raids then increased the emirate’s size; the first to go as far as Corsica occurred in 806.

The caliphate enjoyed increased prosperity during the 10th century. Abd ar-Rahman III united al-Andalus and brought the Christian kingdoms of the north under control by force and through diplomacy. Abd ar-Rahman III stopped the Fatimid advance into Morocco and al-Andalus in order to prevent a future invasion. The plan for a Fatimid invasion was thwarted when Abd ar-Rahman III secured Melilla in 927, Ceuta in 931, and Tangier in 951. In 948, the Idrisid emir Abul-Aish Ahmad recognised the caliphate, although he refused to allow them to occupy Tangier. The Umayyads besieged Tangier in 949 and defeated Abul-Aish, forcing him to retreat. The Umayyads then occupied the rest of northern Morocco. Although another Fatimid invasion of Morocco occurred in 958 under their general, Jawhar. Al-Hassan II had to recognise the Fatimids. The Umayyads responded by invading Idrisid Morocco in 973 with their general, Ghalib. By 974, Al-Hassan II was taken to Cordoba, and the remaining Idrisids recognised Umayyad rule. This period of prosperity was marked by increasing diplomatic relations with Berber tribes in North Africa, Christian kings from the north, and with France, Germany and Constantinople. The caliphate became very profitable during the reign of Abd ar-Rahman III, by increasing the public revenue to 6,245,000 dinars from Abd ar-Rahman II. The profits made during this time were divided into three parts: the payment of the salaries and maintenance of the army, the preservation of public buildings, and the needs of the caliph. The death of Abd ar-Rahman III led to the rise of his 46-year-old son, Al-Hakam II, in 961. Al-Hakam II continued his father’s policy toward Christian kings and North African rebels. Al-Hakam’s reliance on his advisers was greater than his father’s because the previous prosperity under Abd ar-Rahman III allowed al-Hakam II to let the caliphate run by itself. This style of rulership suited al-Hakam II since he was more interested in his scholarly and intellectual pursuits than ruling the caliphate. The caliphate was at its intellectual and scholarly peak under al-Hakam II.

Almanzor successfully continued the military reforms begun by Al-Hakam and his predecessors, covering many aspects. On one hand, he increased the professionalization of the regular army, necessary both to guarantee his military power in the capital and to ensure the availability of forces for his numerous campaigns, one of the sources of his political legitimacy. This policy de-emphasized levies and other non-professional troops, which he replaced with taxes used to support the professional troops-often saqalibas or Maghrebis-which freed the natives of al-Andalus from military service. Recruitment of saqalibas and Berbers was not new, but Almanzor expanded it. On the other hand, he created new units, unlike the regular army of the Caliphate, that were faithful primarily to himself and served to control the capital. Emir Abd al-Rahman I had already used Berbers and saqalibas for a permanent army of forty thousand to end the conflicts that hitherto had plagued the emirate. At the time of Emir Muhammad I, the army reached thirty-five to forty thousand combatants, half of them Syrian military contingents. This massive hiring of mercenaries and slaves meant that, according to Christian chroniclers, “ordinarily the Saracen armies amount to 30, 40, 50, or 60,000 men, even when in serious occasions they reach 100, 160, 300 and even 600,000 fighters.” In fact, it has been argued that, in Almanzor’s time, the Cordovan armies could muster six hundred thousand laborers and two hundred thousand horses “drawn from all provinces of the empire.”

In order to eliminate a possible threat to his power and to improve military efficiency, Almanzor abolished the system of tribal units that had been in decline due to lack of Arabs and institution of pseudo-feudalism on the frontiers, in which the different tribes each had their own commander and that had caused continuous clashes, and replaced it with mixed units without clear loyalty under orders from Administration officials. The nucleus of the new army, however, was formed increasingly by Maghrebi Berber forces. The ethnic rivalries among Arabs, Berbers and Slavs within the Andalusian army were skillfully used by Almanzor to maintain his own power —for example, by ordering that every unit of the army consist of diverse ethnic groups so that they would not unite against him; and thus preventing the emergence of possible rivals. However, once their centralizing figure disappeared, these units were one of the main causes of the 11th-century civil war called the Fitna of al-Andalus. Berber forces were also joined by contingents of well-paid Christian mercenaries, who formed the bulk of Almanzor’s personal guard and participated in his campaigns in Christian territories. Almanzor’s completion of this reform, begun by his predecessors, fundamentally divided the population into two unequal groups: a large mass of civilian taxpayers and a small professional military caste, generally from outside the peninsula.

According to modern studies, these mercenary contingents made it possible to increase the total size of the Caliphal army from thirty or fifty thousand troops in the time of Abd al-Rahman III to fifty or ninety thousand. Others, like Évariste Lévi-Provençal, argue that the Cordoban armies in the field with the Almanzor were between thirty-five thousand and seventy or seventy-five thousand soldiers. Contemporary figures are contradictory: some accounts claim that their armies numbered two hundred thousand horsemen and six hundred thousand foot soldiers, while others talk about twelve thousand horsemen, three thousand mounted Berbers and two thousand sūdān, African light infantry. According to the chronicles, in the campaign that swept Astorga and León, Almanzor led twelve thousand African and five thousand Al Andalus horsemen, and forty thousand infantry. It is also said that, in his last campaigns, he mobilized forty-six thousand horsemen, while another six hundred guarded the train, twenty-six thousand infantry, two hundred scouts or ‘police’ and one hundred and thirty drummers. or that the garrison of Cordoba consisted of 10,500 horsemen and many others kept the northern border in dispersed detachments. However, it is much more likely that the leader’s armies, even in their most ambitious campaigns, may not have exceeded twenty thousand men. It can be argued that until the eleventh century no Muslim army on campaign exceeded thirty thousand troops, while during the eighth century the trans-Pyrenean expeditions totaled ten thousand men and those carried out against Christians in the north of the peninsula were even smaller.

In the time of Emir Al-Hakam I, a palatine guard of 3000 riders and 2000 infantry was created, all Slavic slaves. This proportion between the two types of troops was maintained until Almanzor’s reforms. The massive incorporation of North African horsemen relegated the infantry to sieges and fortress garrisons. This reform led to entire tribes, particularly Berber riders, being moved to the peninsula.

During this time, military industry flourished in factories around Córdoba. It was said to be able to produce a thousand bows and twenty thousand arrows monthly, and 1300 shields and three thousand campaign stores annually.

As for the fleet, its network of ports was reinforced with a new base in the Atlantic, in Alcácer do Sal, which protected the area of Coimbra, recovered in the 980s, and served as the origin of the units that participated in the campaign against Santiago. On the Mediterranean shore, the naval defense was centered at the base of al-Mariya, now Almería. The dockyards of the fleet had been built in Tortosa in 944.

Initially the maritime defense of the Caliphate was led by Abd al-Rahman ibn Muhammad ibn Rumahis, a veteran admiral who had served Al-Hakam II and was Qadi of Elvira and Pechina. He repulsed raids by al-Magus (idolaters) or al-Urdumaniyun (‘men of the north’, vikings), in the west of al-Andalus in mid-971; at the end of that year, when they tried to invade Al Andalus, the admiral left Almería and defeated them off the coast of Algarve. In April 973, he transported the army of Ghalib from Algeciras to subdue the rebellious tribes of the Maghreb and end Fatimid ambitions in that area. As in 997, when the Al Andalus fleet hit the Galician coast, in 985 it had ravaged the Catalans. During the Catalan campaign, Gausfred I, Count of Empurias and Roussillon, tried to gather an army to help the locals but then several flotillas of Berber pirates threatened their coasts, forcing them to stay to defend their lands.

Land transport routes were dotted with strongholds, since ancient Al Andalus dignitaries sought to control communications. Messengers were bought in Sudan and specially trained to handle Almanzor’s messages and to transmit the official reports that his foreign ministries wrote about the annual campaigns.

The Caliphate ruled by Almanzor was a rich and powerful state. According to Colmeiro, it is estimated that in a pre-industrial society, for every million inhabitants, ten thousand soldiers could be mustered. Even assuming the chronicles exaggerated tenfold the real numbers – these speak of eight hundred thousand soldiers – the caliphate could have had eight million inhabitants. Those who use more bullish criteria estimate between seven and ten million, but the population was probably much fewer. Traditionally speaking, around the year 1000, the caliphate occupied four hundred thousand square kilometers and was populated by three million souls. By comparison, the Iberian Christian states comprised one hundred and sixty thousand square kilometers and half a million people.By the 10th century, 75% of the population under the Umayyads had converted to Islam, a number reaching 80% two centuries later. By comparison, at the time of the Muslim invasion, Spain had about four million inhabitants, although there is no shortage of historians who would raise that estimate to seven or eight million.

His realm also had large cities like Córdoba, which surpassed one hundred thousand inhabitants; Toledo, Almería and Granada, which were around thirty thousand; and Zaragoza, Valencia and Málaga, all above fifteen thousand. This contrasted sharply with the Christian north of the peninsula, which lacked large urban centers.

Córdoba was the cultural and intellectual centre of al-Andalus, with translations of ancient Greek texts into Arabic, Latin and Hebrew. During the reign of al-Hakam II, the royal library possessed an estimated 400,000 to 500,000 volumes. For comparison, the Abbey of Saint Gall in Switzerland contained just over 100 volumes. Advances in science, history, geography, philosophy, and language occurred during the Caliphate. Al-Andalus’s prosperity and the caliph’s patronage attracted travelers, diplomats and scholars. They continued the legacy of figures such as Ziryab in the 9th century by bringing in new styles of art, music, and literature from the eastern Islamic world. Cordoba also became a center of culture and high society in its own right. Poets sought the patronage of its court, as with the example of Ibn Darraj al-Qastali, who served as court poet for Abd al-Rahman III, Al-Hakam II, and Almanzor. Other poets, such as Yusuf al-Ramadi, composed works on nature and love. Muwashshah, a form of Andalusi verncular poetry combining vernacular Arabic and the vernacular Romance language, grew more popular during this period. Writers also began to compose histories devoted to the Umayyad dynasty of Al-Andalus, such as Ahmad al-Razi‘s History of the Rulers of al-Andalus. These histories also provided information on the land and its people. Many ideas and myths concerning the history of al-Andalus – including stories about its initial Muslim conquest in the 8th century – began to appear in this period.

Upper-class women also had the resources to receive education and participate in high culture in the domains of poetry and even religion, such as the ‘Aisha ibn Ahmad, who was born form a noble family, and Lubna, a slave in the service of al-Hakam II. Fatima bint Yahya al-Maghami, another woman, was a well-known faqih (expert on Islamic law and jurisprudence), although religious domains were still dominated by men.

The caliph’s official workshops, such as those at Madinat al-Zahra, fabricated luxury products for use at court or as gifts for guests, allies, and diplomats, which stimulated artistic production. Many objects produced in the caliph’s workshops later made their way into the collections of museums and Christian cathedrals in Europe. Among the most famous objects of this period are ivory boxes which are carved with vegetal, figurative, and epigraphic motifs. Notable surviving examples include the Pyxis of al-Mughira, the Pyxis of Zamora, the Leyre Casket. The caliphal workshops also produced fine silks, including tiraz textiles, ceramics, and leatherwork. Metalwork objects were also produced, of which the most famous surviving piece is the so-called “Cordoba Stag”, a bronze fountain spout carved in the form of a stag which was made at Madinat al-Zahra and preserved by the Archeological Museum of Cordoba. Two other bronze examples of similar craftsmanship, shaped like deers, are kept at the National Archeological Museum in Madrid and the Islamic Art Museum in Doha. While the production of ivory and silk objects largely stopped after the Caliphate’s collapse, production in other mediums like leather and ceramic continued in later periods.

Marble was also carved for decorative elements in some buildings, such as wall paneling and window grilles. One of the most prolific types of marble craftsmanship were capitals, which continued the general configuration of Roman Corinthian capitals but were deeply carved with ataurique and Islamic vegetal motifs in a distinctive style associated with the caliphal period. These capitals later became prized spolia and can be found in later buildings across the region built under the Almoravids and Almohads. Another notable example is a marble basin, now kept at the Dar Si Said Museum in Marrakesh, which was crafted at Madinat al-Zahra between 1002 and 1007 to serve as ablutions basin and dedicated to ‘Abd al-Malik, the son of al-Mansur, before being shipped to Morocco and re-used in new buildings.

The economy of the caliphate was diverse and successful, with trade predominating. Muslim trade routes connected al-Andalus with the outside world via the Mediterranean. Industries revitalized during the caliphate included textiles, ceramics, glassware, metalwork, and agriculture. The Arabs introduced crops such as rice, watermelon, banana, eggplant and hard wheat. Fields were irrigated with water wheels. Some of the most prominent merchants of the caliphate were Jews. Jewish merchants had extensive networks of trade that stretched the length of the Mediterranean Sea. Since there was no international banking system at the time, payments relied on a high level of trust, and this level of trust could only be cemented through personal or family bonds, such as marriage. Jews from al-Andalus, Cairo, and the Levant all intermarried across borders. Therefore, Jewish merchants in the caliphate had counterparts abroad that were willing to do business with them.

Religion in Al-Andalus around the 11th century

The caliphate had an ethnically, culturally, and religiously diverse society. A minority of ethnic Muslims of Arab descent occupied the priestly and ruling positions, another Muslim minority were primarily soldiers and muladi converts were found throughout society. Jews comprised about ten percent of the population: little more numerous than the Arabs and about equal in numbers to the Berbers. They were primarily involved in business and intellectual occupations. The Christian minority (Mozarabs) professed by and large the Visigothic rite. The Mozarabs were in a lower strata of society, heavily taxed with few civil rights and culturally influenced by the Muslims. Ethnic Arabs occupied the top of the social hierarchy; Muslims had a higher social standing than Jews, who had a higher social standing than Christians. Christians and Jews were considered dhimmis, required to pay jizya (a protection tax).

Half of the population in Córdoba is reported to have been Muslim by the 10th century, with an increase to 70 percent by the 11th century. That was due less to local conversion than to Muslim immigration from the rest of the Iberian Peninsula and North Africa. Christians saw their status decline from their rule under the Visigoths, meanwhile the status of Jews improved during the Caliphate. While Jews were persecuted under the Visigoths, Jewish communities benefited from Umayyad rule by obtaining more freedom, affluence and a higher social standing.

According to Thomas Glick, “Despite the withdrawal of substantial numbers during the drought and famine of the 750’s, fresh Berber migration from North Africa was a constant feature of Andalusi history, increasing in tempo in the tenth century. Hispano-Romans who converted to Islam, numbering six or seven millions, comprised the majority of the population and also occupied the lowest rungs on the social ladder.” It is also estimated that the capital city held around 450,000 people, making it the second largest city in Europe at the time.

The death of al-Hakam II in 976 marked the beginning of the end of the caliphate. Before his death, al-Hakam named his only son Hisham II successor. Although the 10-year-old child was ill-equipped to be caliph, Al-Mansur Ibn Abi Aamir (top adviser to al-Hakam, also known as Almanzor), who had sworn an oath of obedience to Hisham II, pronounced him caliph. In 996, Almanzor sent an invasion force to Morocco. After three months of struggle, his forces retreated to Tangier. Almanzor then sent a powerful reinforcement under his son Abd al-Malik. The armies clashed near Tangier. The Umayyads would enter Fes on October 13, 998 once the gates of the city were opened. Almanzor had great influence over Subh, the mother and regent of Hisham II. Almanzor, along with Subh, isolated Hisham in Córdoba while systematically eradicating opposition to his own rule, allowing Berbers from Africa to migrate to al-Andalus to increase his base of support. While Hisham II was caliph, he was merely a figurehead. He, his son Abd al-Malik (al-Muzaffar, after his 1008 death) and his brother (Abd al-Rahman) retained the power nominally held by Caliph Hisham. However, during a raid on the Christian north a revolt tore through Córdoba and Abd al-Rahman never returned.

The title of caliph became symbolic, without power or influence. The death of Abd al-Rahman Sanchuelo in 1009 marked the beginning of the Fitna of al-Andalus, with rivals claiming to be the new caliph, violence sweeping the caliphate, and intermittent invasions by the Hammudid dynasty. Beset by factionalism, the caliphate crumbled in 1031 into a number of independent taifas, including the Taifa of Córdoba, Taifa of Seville and Taifa of Zaragoza. The last Córdoban Caliph was Hisham III (1027–1031).

Caliphs of Córdoba | |

Umayyad Caliphs of Córdoba | |

Caliph | Reign |

16 January 929 – 15 October 961 | |

15 October 961 – 16 October 976 | |

16 October 976 – 1009 | |

1009 | |

1009–1010 | |

1010 – 19 April 1013 | |

1013–1016 | |

1017 | |

Hammudid Caliphs of Córdoba | |

1016–1018 | |

1018–1021 | |

1021–1023 | |

1023 | |

Umayyad Caliphs of Córdoba (Restored) | |

1023–1024 | |

1024–1025 | |

Hammudid Caliphs of Córdoba (Interregnum) | |

1025–1026 | |

Umayyad Caliphs of Córdoba (Restored) | |

1026–1031 | |

End of the Caliphate | |

” ‘O’ sacred place of Cordoba, you exist because of Ishq

Ishq that’s wholly eternal, which does not come and go”

The mosque was commissioned by Abd Rahman I around 785, more than 1100 years before Iqbal visited it. It then continued to be developed for many years since.

It was a very different era with Europe in the dark ages, and the Muslim civilisation flourishing. According to the World Heritage Centre, the mosque “represents a unique artistic achievement due to its size and the sheer boldness of the height of its ceilings. It is an irreplaceable testimony of the Caliphate of Cordoba and it is the most emblematic monument of Islamic religious architecture.”

It goes on to say that it was “a very unusual type of mosque that bears witness to the presence of Islam in the West.”

Other accounts of the mosque are similar in praising its beauty and its famous pillars, arches, and dome. As Iqbal said:

Your foundations are lasting, your columns countless

Like a cluster of palms in the desert of Syria

After the fall of Muslims in Spain, the mosque was converted into a cathedral in around 1246 and a giant nave was built on it. The cathedral, however, does not elicit the same praise from its observers.

Iqbal, who visited the mosque long after it had been converted to a cathedral, was fortunate that he was allowed to offer his prayers in the mosque because, to my surprise, I found that the Spanish authorities strictly prohibit it now.

The more I read about the mosque, the more information I found on its architecture and history — so much information in fact that I felt I was losing sight of what the mosque meant to Iqbal.

I knew that architectural achievement alone meant little to Iqbal. After all, there was Taj Mahal in India, which, despite being a fascination for many poets, failed to get his attention.

The Ghazi, these mysterious bondsmen Of Thine,

To whom Thou hast granted zest for Divinity.

Deserts and oceans fold up at their kick,

And mountains shrink into mustard seeds.

Indifferent to the riches of the world it makes,

What a curious thing is the joy of love?

Martyrdom is the desired end of the Momin,

Not spoils of war, kingdom and rule!

For long has tulip in the garden been waiting,

It needs a robe dipped in Arab blood.

Thou made the desert dwellers absolutely unique,

In thought, in perception, in the morning Adhan;

What, for centuries, life had been seeking,

It found the warmth in the hears of these men;

Death is the opener of the heart’s door,

It’s not the journey’s end in their sight.

Revive, once again, in the heart of the Momin,

The lightning that was in the prayer of ‘Leave Not’.

Wake up ambition in the breasts, O’ Lord!

Transform, the glance of the Momin into a sword.

قطرۂ خُونِ جگر، سِل کو بناتا ہے دل

خُونِ جگر سے صدا سوز و سُرور و سرود

تیری فضا دل فروز، میری نوا سینہ سوز

تجھ سے دِلوں کا حضور، مجھ سے دِلوں کی کشود

عرشِ معلّیٰ سے کم سینۂ آدم نہیں

گرچہ کفِ خاک کی حد ہے سِپہرِ کبُود

پیکرِ نُوری کو ہے سجدہ میّسر تو کیا

اس کو میّسر نہیں سوز و گدازِ سجود

کافرِ ہندی ہُوں مَیں، دیکھ مرا ذوق و شوق

دل میں صلٰوۃ و دُرود، لب پہ صلوٰۃ و دُرود

شوق مری لَے میں ہے، شوق مری نَے میں ہے

نغمۂ ’اللہھوٗ‘ میرے رَگ و پَے میں ہے

Oh shrine of Cordova, thou owes; existence to love.

Deathless in all its being, stranger to Past and Present.

Color or brick and stone, speech or music or song,

Only the heart’s warm blood feeds the craftsman/s design;

One drop of heart’s blood lends marble a heating heart,

Out of the heart’s blood flow out warmth, music and mirth.

Thine the soul-quickening air, mine the soul-quickening verse,

From thee the pervasion of men’s hearts, from me the opening of men’s hearts.

Inferior to the Heaven of Heavens, by no means the human breast is,

Handful of dust though it be, hemmed in the azure sky.

What if prostration be the lot of the heavenly host?

Warmth and depth of prostration they do not ever feel.

I’ a heathen of Ind, behold my fervour and my ardour,

Salat! And Durood fill my soul, Salat ad Darood are on my lips!

Fervently sounds my voice, ardently sounds my lute,

Allah Hu, like a song, thrilling through every vein!

The Al-Hambra is a palace and fortress complex located in Granada, Andalusia, Spain. It was originally constructed as a small fortress in 889 CE on the remains of ancient Roman fortifications, and then largely ignored until its ruins were renovated and rebuilt in the mid-13th century by the Arab Nasrid Amir Muhammad bin Al-Ahmar of the Empire of Granada.

Al-Hambra’s last flowering of Islamic palaces was built for the final Muslim emirs in Spain during the decline of the Nasrid Dynasty.

2022 © Copyrights Qurtaba City.